Challenges in India

One of the distinguishing features of the cities which have launched public bicycle schemes is that they are fully committed to the principles of sustainable transport which is reflected in their policies and projects. These cities and their political representatives have realised, in some cases the hard way, that building more roads, bridges and flyovers does not help to solve traffic problems, it worsens them. They have, therefore, started to make concerted efforts to improve public transport and make walking and cycling safe, convenient and attractive. They have also imposed various disincentives for personal motorised modes of transport. Some of these are congestion charging, high parking rates and limited parking for vehicles, and re-allocation of road space for cycle tracks, wider footpaths and public spaces. Public bicycle schemes are but one more tool in this wide array of measures undertaken by these cities.

One of the distinguishing features of the cities which have launched public bicycle schemes is that they are fully committed to the principles of sustainable transport which is reflected in their policies and projects. These cities and their political representatives have realised, in some cases the hard way, that building more roads, bridges and flyovers does not help to solve traffic problems, it worsens them. They have, therefore, started to make concerted efforts to improve public transport and make walking and cycling safe, convenient and attractive. They have also imposed various disincentives for personal motorised modes of transport. Some of these are congestion charging, high parking rates and limited parking for vehicles, and re-allocation of road space for cycle tracks, wider footpaths and public spaces. Public bicycle schemes are but one more tool in this wide array of measures undertaken by these cities.

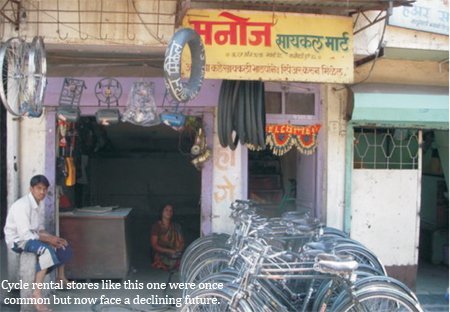

In India, however, cities still continue to think of cycles as being outdated or a recreational pass-time at best, and not really an integral part of the formal transport system. Politicians and administrators alike are therefore, unwilling to make the kind of serious commitment to the planning, financing and implementation of projects such as public bicycle schemes.

Financing Public Bicycle Schemes

Much like public transport, it is not possible for public bicycle schemes to be financially self-supporting and must, therefore, be publicly funded. Most importantly, the cycle stations must be located in public spaces, just like bus stops. The investment in the infrastructure is substantial, with well designed stations/kiosks, good quality bicycles and the sophisticated IT system that helps to run the scheme. It requires a central command centre and the usual administrative set-up. User fees have to be nominal in order to attract users.

Much like public transport, it is not possible for public bicycle schemes to be financially self-supporting and must, therefore, be publicly funded. Most importantly, the cycle stations must be located in public spaces, just like bus stops. The investment in the infrastructure is substantial, with well designed stations/kiosks, good quality bicycles and the sophisticated IT system that helps to run the scheme. It requires a central command centre and the usual administrative set-up. User fees have to be nominal in order to attract users.

Worldwide, three major models of financing public bicycle schemes have emerged. In Europe, many schemes are funded through advertising. V?lib? is one such scheme. Not surprisingly, outdoor advertising agencies are involved in such projects. However, this requires a tightly controlled outdoor advertisement policy, leading to high rates for outdoor billboards, enough to cross-subsidise the bicycle scheme. This is unfortunately not the case in India. The second model is corporate sponsorship. The New York and London schemes are examples of this, with Citibank and Barclays Bank sponsoring these schemes respectively. This requires the corporate sector to see these projects as being worthy of being sponsored, much like the sponsorship of cricket tournaments. This can happen only when the city is able to market the scheme and work with such potential sponsors. Mayors of cities act as business promoters to pull off these deals. Once again, this is not how Indian cities operate. The third common model is for public bicycle schemes to be a part of the public transport system of the city. Many of the Chinese cities operate their public bicycle schemes through their public transport companies. This makes sense, since the bicycles can actually integrate with the bus/metro systems and act as feeders or last mile connectors. Once again, public transport companies in Indian cities, where they even exist, are poorly funded and managed, and would be unlikely to have the capacity to plan and operate these systems.

Nothing compares to the simple pleasure of riding a bike.

? John F Kennedy

However, with the advent of Metro rail systems in India, there seems to be an opportunity for the Metro Rail Corporations to take up public bicycle schemes, starting with cycle stations located at the Metro stations and common origins and destinations, eventually spreading in the city.

However, with the advent of Metro rail systems in India, there seems to be an opportunity for the Metro Rail Corporations to take up public bicycle schemes, starting with cycle stations located at the Metro stations and common origins and destinations, eventually spreading in the city.

There can be no denying that public bicycle schemes are important for Indian cities. They have the potential to make cycling ?cool? again and attract young and casual riders who are generally reluctant to take up cycling. They can be useful to promote tourism, and not surprisingly, cities like Mysore and Jaipur are planning them. Most cities could plan for such schemes in their historical/old city areas where often, narrow streets make motorised traffic impractical.

There is, however, a great need to educate politicians and administrators about public bicycle schemes and offer financial support to cities willing to take them up, much in the same way that the Ministry of Urban Development funded the purchase of buses under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM). The publication of the toolkits is the first small step in this direction, but a lot more needs to be done. There is a need for the private sector, especially the bicycle manufacturers, to take the lead in supporting and promoting these schemes; so far they have been passive onlookers. And as is often the case, the successful implementation of such a scheme in just one city may well trigger an avalanche in other cities.

(Ranjit, an alumni of IIT Kanpur and Cornell University, is involved in various urban transport initiatives with his current interests including non-motorised transport, street design and Bus Rapid Transit Systems. He has also worked as an IT consultant for several years in the U.S. before returning to India.)

(Ranjit, an alumni of IIT Kanpur and Cornell University, is involved in various urban transport initiatives with his current interests including non-motorised transport, street design and Bus Rapid Transit Systems. He has also worked as an IT consultant for several years in the U.S. before returning to India.)

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress