Sonal Shah

A lot needs to be done to improve bus transportation for women and create a safe, reliable, accessible and affordable travel journey, states Sonal Shah, expert on Sustainable and Gender Equitable Transport.

You have been contributing to quality in mobility and public transport especially for women. What have been the prime drivers in this transition?

My journey with gender and cities started very early. Actually, I got interested in feminist studies back in architecture school, and also pursued it in my graduate education. But the opportunity to work on gender and mobility really came when I was working with WRI India. The main catalyst at that time was the rape and death of a young woman in a bus in Delhi, and it really highlighted how transport was unsafe for women and therefore a few of us in WRI India began to think about what could be done.

When the masterplan for Mumbai was getting revised, I had the opportunity to look at how gender could be incorporated in it. We also managed to incorporate gender inclusive urban planning guidelines in the URDPFI guidelines, a first for India. Additionally, I led a team to fundraise for a project on women’s safety in public transport in Bhopal. When I was in ITDP, our efforts got crystalized into co-creating a policy brief on Women and Transport in Indian Cities back in 2017, the first of its kind in India. We made concrete recommendations on gender-inclusive mobility indicators that could be introduced in comprehensive mobility plans.

About The Urban Catalysts

The Urban Catalysts was incorporated in 2018, and over the last four and a half years, we have institutionalized a gender lens in mass transit projects through Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Action Plans. We have also prepared a Women’s Access and Mobility Plan (WAMP) for 3 cities in Bihar: Patna, Gaya and Muzaffarpur, which is another first for India, and are going to publish this research soon.

We have also advised on incorporating a gender lens in the bus rapid transit system in Amman (Jordan) and advised the Gender Working Group in Tbilisi City Hall (Georgia) on gender-inclusive urban planning indicators. Over the last 13 months, we have led a team in the process of creating climate resilient, gender and socially inclusive public open space guideline for secondary towns in Bangladesh, and conducted capacity development workshops at the city and national level.

How important it is to have gender-responsive urban planning and infrastructure?

Women constitute a majority of pedestrians in Indian cities. To design for sustainable transport, we must plan for pedestrians, while recognizing the needs of different groups of women and gender minorities. Specifically, gender-based violence, safety and sexual harassment in public spaces as well as care giving role predominantly performed by women in Indian cities.

Caregivers and senior citizens are unnoticed pedestrians. They may take a little longer to cross, so pedestrian signals must be provided and account for this time.

In 2011, we had 5.6 million women walking between zero to five kilometers to their workplace. These distances could be covered easily by cycling. However, women constitute less than 5% of all cyclists. Though there are many cycling programmes for girls in the rural areas, but there aren’t many female cyclists in cities. Hence one needs to ask, do women have access to bicycles, is it safe to cycle? Do they know how to cycle, are cycles designed for women? Do bicycle sharing systems consider women’s travel destinations and entry barriers? Dedicated cycle tracks, safe crossings, programmes to encourage women and girls in cities to bicycle, bicycle sharing schemes that address gendered travel and entry barriers and most importantly awareness and behaviour change programmes can help.

Public Transport

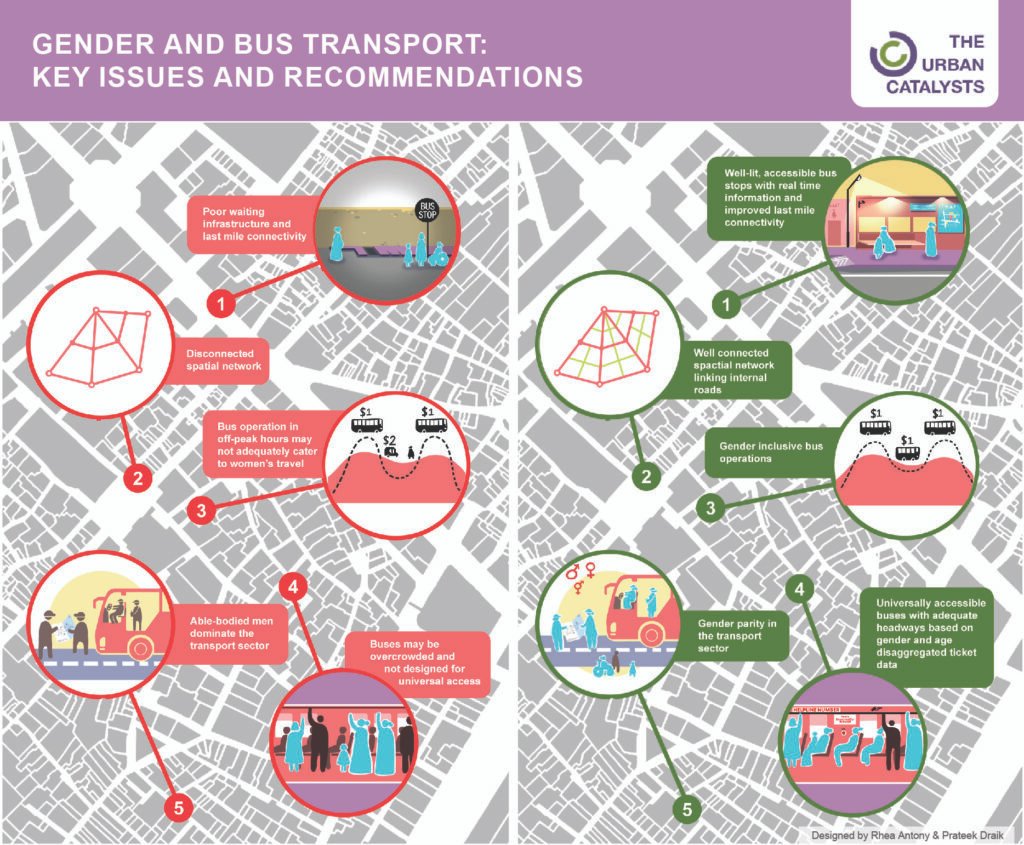

A lot needs to be done to improve bus transportation for women and create a safe, reliable, accessible and affordable travel journey: access to and from bus stops/ terminals, waiting, boarding and alighting and travel inside buses. In our research with 800 resource poor women living in urban villages, resettlement colonies, informal settlements in Delhi, The Urban Catalysts observed that less than 10 percent of women had access to any type of phone. This made smart phone enabled real time information inaccessible to them. Hence SMS-based messaging system to check the estimated time of arrival for the bus needs to be developed. This could reduce the waiting time at the bus stop.

Even in Delhi, which provides fare-free transport in buses, close to 60 percent of resource poor women’s trips in the morning were by shared paratransit. Buses would often not stop for them, and street vendors and waste pickers were not allowed to board buses. Bus operations and schedules need to cater to women’s mobility, which the mohalla bus scheme may have the potential to address.

How can we have more women drivers, conductors through concerted reforms in regulations, depot infrastructure, work schedules, grievance redress mechanisms and culture?

Further, our research in Bihar revealed that a majority of paratransit passengers were women. There is a need to design integrated systems that center women, girls and gender minorities.

We have a long way to go…

We need sustained and bold action towards sustainable mobility on one hand and ensure that gender is centered in all sustainable transport. That means allocating budgets, building capacity in our urban development, transport, women and child and social welfare offices and ensuring coordinated action as the transport sector is very fragmented.

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress

TrafficInfraTech Magazine Linking People Places & Progress