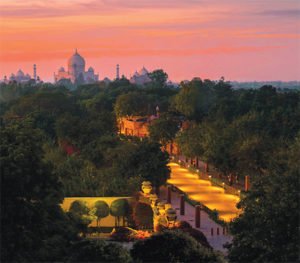

In India, heritage is perceived as a valuable resource and hence the approach to urban redevelopment in old city areas has been based singularly on this premise. It is inherited but cannot be ‘consumed’ and therefore must be handed over preferably with enrichment, to future generations. Taj Ganj is a four centuries old district. Once an integral part of the monument complex, sharing the peripheral skyline with the Taj Mahal. The Taj Ganj Urban redevelopment project attempts to sew together disparate urban edges that are commercial, institutional, parks, bazaars, old city fabrics and slums and thus present new perspectives of the city that emerge from the multiple layers that have been created over time.

In India, heritage is perceived as a valuable resource and hence the approach to urban redevelopment in old city areas has been based singularly on this premise. It is inherited but cannot be ‘consumed’ and therefore must be handed over preferably with enrichment, to future generations. Taj Ganj is a four centuries old district. Once an integral part of the monument complex, sharing the peripheral skyline with the Taj Mahal. The Taj Ganj Urban redevelopment project attempts to sew together disparate urban edges that are commercial, institutional, parks, bazaars, old city fabrics and slums and thus present new perspectives of the city that emerge from the multiple layers that have been created over time.

It proposes a coherent but nonuniform urban design along stretches leading to it, giving priority to non-motorised mobility through a radical change in the visual texture of the place. Urban interventions at specific nodes such as the Kutta park, a pavilion or two, pause spots, and viewing points make up the value additions to this area.

Street as space…a spine

Street as space…a spine

The active ‘streets as connectors’ align visitors to the ethos of the ordinary people as heirs to the cultural legacy along with the Taj. Like all roads, they lead to it; but more importantly through this, begin urban networking and eventually they weave the fabric of the entire city of Agra.

The street emerging from the East Gate is textured in cobble of Red Agra, the local stone, up to a distance of zero–vehicular 500 metres zone. Then up to 1200 metres, the cobble continues in granite for the restricted access of motorized vehicles. A 2-way carriageway of width 7.5 metres flanked by footpaths and cycle paths 5 metres wide extends up to the cobbled zone. A walk along this tree-lined path that extends up to shops enroute and is supplied with public conveniences, seats, kiosks, control rooms etc.

[box type=”shadow” ]

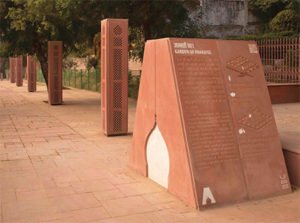

The way-finding within Taj Ganj and at all gates has been done to make navigation a meaningful and enjoyable experience, the way-finding signage becomes a precursor to creating varied perspectives of the city

[/box]

Cobbling ensures that vehicular traffic explicitly slows down; backed by footpaths merging seamlessly with the road but delineated by bollards, the street is a walker’s paradise. But allowing for multiple modes of transport, eac h with its speed and its own system of perception operating simultaneously, the vision for this urban renewal program incorporates non-motorised ones as e-rickshaws and even traditional horse carriages called ‘Tongas’. The urban floor plane has been laid in the local and identifiable Red Agra stone and ruby red granite.

Cobbling ensures that vehicular traffic explicitly slows down; backed by footpaths merging seamlessly with the road but delineated by bollards, the street is a walker’s paradise. But allowing for multiple modes of transport, eac h with its speed and its own system of perception operating simultaneously, the vision for this urban renewal program incorporates non-motorised ones as e-rickshaws and even traditional horse carriages called ‘Tongas’. The urban floor plane has been laid in the local and identifiable Red Agra stone and ruby red granite.

The homogeneity of materials makes the street and its furniturelamp posts, bollards, benches and the likes provide a cognitive setting to the wondrous monument whose second name is harmony. The lamp post is a sculptural element made in the same stone as the rest of the street furniture — incorporating the proportions of the framing minarets of the Taj and the profile of its graceful dome. Through the use of Jaalis-perforated screens and the play of light, the lamps dot the street, add a measure of romanticism to its character even while placing the monument centre stage.

A project by archohm consults.

Pictures by Andre J Fanthome