This International Women’s Day, the call for a gender- balanced world needs to better the balance by asking women and girls what they want from their urban mobility systems. Policies designed and implemented to improve transport infrastructure and services cannot be assumed to automatically benefit women. Over the last five years, the emphasis on gender responsive transport in India has predominantly focused on increasing surveillance through tracking women’s movement and CCTV cameras, even though research has emphasized that women’s urban mobility depends on the quality of public spaces as well as service reliability, scheduling, affordability, and physical and personal safety of public transport. How do we make transport services respond to women and girls’ needs?

This International Women’s Day, the call for a gender- balanced world needs to better the balance by asking women and girls what they want from their urban mobility systems. Policies designed and implemented to improve transport infrastructure and services cannot be assumed to automatically benefit women. Over the last five years, the emphasis on gender responsive transport in India has predominantly focused on increasing surveillance through tracking women’s movement and CCTV cameras, even though research has emphasized that women’s urban mobility depends on the quality of public spaces as well as service reliability, scheduling, affordability, and physical and personal safety of public transport. How do we make transport services respond to women and girls’ needs?

Gendered data can be a powerful means to establish baselines, inform planning priorities, measure transport inequity as well as monitor outcomes. In 2011, the Census of India collected gender disaggregated data on the mode of travel and distance to place of work for other workers i.e. cultivators, non-farm workers and those not engaged in household industry. While limited to work trips, this data revealed that close to half of all urban female workers walked, cycled and used bus- based public transport. It also showed how women were walking long distances, further adding to their time poverty or limited time for leisure and discretionary activities. Around 2 million women workers walked 2-5 kilometres every day, distances that could be covered in half the time by cycling. Similarly, another million women walked 6-10 kilometres, which could be served by bus-based public transport and rickshaws, among others.

While the Census revealed insights on how women traveled to work, were these modes preferred by them or because of a lack of other alternatives? A recent survey by the Ola Mobility Institute (OMI) across 11 cities found that only four percent of women preferred non-motorized transport as a commuting mode. A meagre seven percent perceived that seamless footpaths were available throughout their city and 69 percent of women felt that there were no cycle tracks or only along a few roads.

Why might this be? Studies have shown how crowded, dark, high, uneven and unshaded footpaths affect women disproportionately, as they may feel unsafe, be prone to harassment and are often accompanied by dependents (either children or the elderly). The Safe City Project for Lucknow proposes “safety measures in buses” including cameras and street lighting in “hotspot areas”. While it is a beginning, piecemeal attempts to improve infrastructure by focusing only on street lighting are also insufficient. Do women not desire wide, shaded, universally accessible, well-lit footpaths and safer crossings? Some cities such as Chennai, Bengaluru, and Pune have made strides towards improving pedestrian infrastructure. We need to ensure that women’s voices are a part of this process. Supporting amenities such as public toilets, seating, spaces for street vendors and play areas for children should be included along with employment opportunities for women in street redesign projects – either in construction or as street vendors, traffic police and security personnel.

However, women are not a homogenous group, and alongside gender, individual monthly income is another parameter that defines mobility preferences. The 2018 OMI survey revealed that public transport was preferred by 50 percent of women earning less than Rs 15,000 per month, which reduced to two percent for those earning more than Rs 100,000 per month. While lower-income women’s expectation from public transport prioritized better coverage followed by affordability and frequency of public transport, higher income women desired comfort over affordability and coverage, necessitating a nuanced approach to the provision and pricing of public transport services.

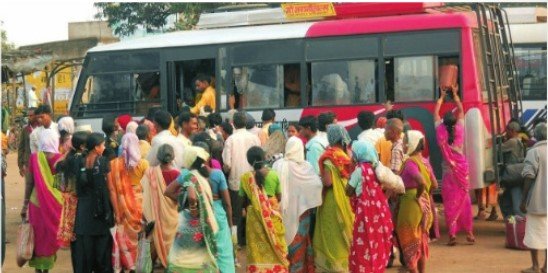

Simultaneously, while gruesome incidents of violence against women have received attention in mainstream media, only three percent of the women respondents of the 2018 OMI Survey felt that public transport was very unsafe. Most women (88 percent) perceived public transport as somewhat unsafe or safe. This may indicate that women face daily harassment such as staring, groping, catcalls, whistling, rude behavior which needs to be addressed. Can CCTV cameras capture this form of harassment in crowded public transport in the peak hours? Transport authorities and the Police need to work together to create an effective complaints redressal systems and sustained communication campaigns with zero tolerance approach to sexual harassment to encourage women to complain and bystanders to intervene. In London, the Metropolitan Police Service, British Police and Transport for London created the Report It, Stop It campaign encouraging people to report instances of sexual harassment. In 2015-16, 1,716 sexual offences were reported, with an increase of 31 percent compared to the previous year resulting in more than 500 arrests. Standard operating procedures and gender sensitization trainings of frontline workers can also play a role in preventing and addressing women and girls’ daily harassment. In Delhi, gender sensitization trainings were conducted with 250,000 commercial vehicle drivers. These now need to be evaluated, improved and conducted on a regular basis.

In Cairo, a gender assessment of public transport found that overcrowding, harassment, multiple transfers, long waits and travel times, high fares, and unsafe driving behaviors were issues of great concern to women. This study has been used to inform the design of the bus rapid transit system such as an increased bus fleet, designated areas for women on each bus; seating for pregnant women, the elderly, people with disabilities, and adults with small children; cameras on BRT buses to monitor harassment and violence; and a complaint and redress system.

Women and girls are constantly making decisions about how they travel. Singular responses and “smart” solutions which focus primarily on increasing surveillance do not address how women combine work and care- related trips and the increased costs resulting from these, their lack of access to bicycles and safer cycling environments, discomfort and daily harassment on streets and crowded public transport. We need data – qualitative and quantitative – to include women’s mobility in planning processes and ensure that transport investments benefit them. Urban planning and transport cannot change societal mindsets. Let it not become a barrier but an enabler for women to participate in the workforce and to live a fuller life.